Thomas Jefferson - Democratic Republican

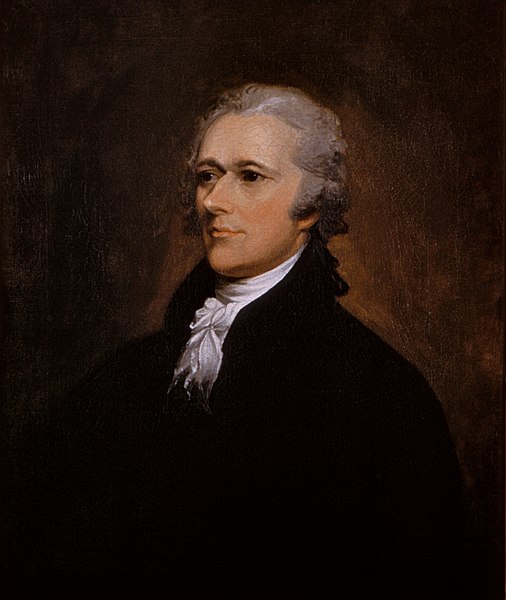

Alexander Hamilton - Federalist

Politics in America has never been straight forward by any stretch of the imagination. However it has had a few fairly consistent threads through out it's history. The main ones being those having to do with who each group and/or party was being represented. The first political parts were the Federalists and Republican AKA Democratic Republicans.

The Federalist policies called for a national bank, tariffs, and good relations with Britain as expressed in the Jay Treaty negotiated in 1794. Their political opponents, the Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, denounced most of the Federalist policies, especially the bank, and vehemently attacked the Jay Treaty as a sell-out of republican values to the British monarchy. The Jay Treaty passed, and indeed the Federalists won most of the major legislative battles in the 1790s. They held a strong base in the nation's cities and in New England.

......

Intellectually, Federalists, while devoted to liberty held profoundly, conservative views atuned to the American character. As Samuel Eliot Morison explained, They believed that liberty is inseparable from union, that men are essentially unequal, that vox populi [voice of the people] is seldom if ever vox Dei [the voice of God], and that sinister outside influences are busy undermining American integrity.[25] Historian Patrick Allitt concludes that Federalists promoted many conservative positions, including the rule of law under the Constitution, republican government, peaceful change through elections, judicial supremacy, stable national finances, credibile and active diplomacy, and protection of wealth. [26].

The Federalists were dominated by businessmen and merchants in the major cities who supported a strong national government. The party was closely linked to the modernizing, urbanizing, financial policies of Alexander Hamilton. These policies included the funding of the national debt and also assumption of state debts incurred during the Revolutionary War, the incorporation of a national Bank of the United States, the support of manufactures and industrial development, and the use of a tariff to fund the Treasury. In foreign affairs the Federalists opposed the French Revolution, engaged in the "Quasi War" (an undeclared naval war) with France in 1798–99, sought good relations with Britain and sought a strong army and navy. Ideologically the controversy between Republicans and Federalists stemmed from a difference of principle and style. In terms of style the Federalists distrusted the public, thought the elite should be in charge, andfavored national power over state power.

Where in the Demoractic Republican party, especially under Jefferson was supported more by the land owners and farmers and plantation owners in the south.Jefferson formed the party to oppose the economic and foreign policies of the Federalists, a party created a year or so earlier by Hamilton to promote the Treasury policies of the Washington administration. The new party opposed the Jay Treaty of 1794 with Britain (then at war with France) and supported good relations with France (until Napoleon became a dictator after 1799). The party insisted on a strict construction of the Constitution, and denounced many of Hamilton's measures (especially the national bank) as unconstitutional. The party was strongest in the South and weakest in the Northeast; it favored states' rights and the primacy of the yeoman farmer over bankers, industrialists, merchants, and investors.

Republicans distrusted Britain, bankers, merchants and did not want a powerful national government. The Federalists, notably Hamilton, were distrustful of "the people," the French, and the Republicans.[27

As time went on, the Federalists lost appeal with the average voter and were generally not equal to the tasks of party organization; hence, they grew steadily weaker as the political triumphs of the Republican Party grew. For economic and philosophical reasons, the Federalists tended to be pro-British – the United States engaged in more trade with Great Britain than with any other country – and vociferously opposed Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807 and the seemingly deliberate provocation of war with Britain by the Madison Administration. During "Mr. Madison's War",

as they called it, the Federalists attempted a comeback but the patriotic euphoria that followed the war undercut their pessimistic appeals.

as they called it, the Federalists attempted a comeback but the patriotic euphoria that followed the war undercut their pessimistic appeals.

After 1816 the Federalists had no national influence apart from John Marshall's Supreme Court. They had some local support in New England, New York, eastern Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware. After the collapse of the Democratic-Republican Party in the course of the 1824 presidential election, most surviving Federalists (including Daniel Webster) joined former Democratic-Republicans like Henry Clay to form the National Republican Party, which was soon combined with other anti-Jackson groups to form the Whig Party. Some former Federalists like James Buchanan and Roger B. Taney became Jacksonian Democrats. The name "Federalist" came increasingly to be used in political rhetoric as a term of abuse, and was denied by the Whigs, who pointed out that their leader Henry Clay was the Republican party leader in Congress during the 1810s.

After the fall of the Federalist Party, those that were left formed the Whig Party.

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s[1], the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party. In particular, the Whigs supported the supremacy of Congress over the presidency, and favored a program of modernization and economic protectionism. This name was chosen to echo the American Whigs of 1776, who fought for independence, and because "Whig" was then a widely recognized label of choice for people who saw themselves as opposing autocratic rule.[2] The Whig Party counted among its members such national political luminaries as Daniel Webster, William Henry Harrison, and their preeminent leader, Henry Clay of Kentucky. In addition to Harrison, the Whig Party also counted four war heroes among its ranks, including Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. Abraham Lincoln was the chief Whig leader in frontier Illinois.

In its two decades of existence, the Whig Party saw two of its candidates, William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, elected president. Both, however, died in office. John Tyler became president after Harrison's death, but was expelled from the party. Millard Fillmore, who became president after Taylor's death, was the last Whig to hold the nation's highest office.

The Whigs were modernizers who saw President Andrew Jackson as a dangerous man on horseback with a reactionary opposition to the forces of social, economic and moral modernization. Most of the founders of the Whig party had supported Jeffersonian democracy and the Democratic-Republican Party. The Republicans who formed the Whig party, led by Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams, drew on a Jeffersonian tradition of compromise and balance in government, national unity, territorial expansion, and support for a national transportation network and domestic manufacturing. Jacksonians looked to Jefferson for opposition to the National Bank and internal improvements and support of egalitarian democracy and state power. Despite the apparent unity of Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans from 1800 to 1824, ultimately the American people preferred partisan opposition to popular political agreement.[4]

The Whigs appealed to voters in every socio-economic category, but proved especially attractive to the professional and business classes: doctors, lawyers, merchants, ministers, bankers, storekeepers, factory owners, commercially-oriented farmers and large-scale planters. In general, commercial and manufacturing towns and cities voted Whig, save for strongly Democratic precincts in Irish Catholic and German immigrant communities; the Democrats often sharpened their appeal to the poor by ridiculing the Whigs' aristocratic pretensions. Protestant religious revivals also injected a moralistic element into the Whig ranks[6].

And I'll bet you thought mud slinging was a modern invention. The Whig party lasted from 1833 to 1856 as deep fishers deveoped along the lines concerning slavery. Most especially with it expanding ito the new territories. And with is desolution came the party that is the current Republican Party. With the Democratic Republicans being call now the Democratic Party.

Founded in northern states in 1854 by anti-slavery activists, modernizers, ex-Whigs and ex-Free Soilers, the Republican Party quickly became the principal opposition to the dominant Democratic Party. It first came to power in 1860 with the election of Abraham Lincoln to the Presidency and oversaw the American Civil War and Reconstruction.[2]

The first official party convention was held on July 6, 1854 in Jackson, Michigan. The Republicans' initial base was in the Northeast and the upper Midwest. With the realignment of parties and voters in the Third Party System, the strong run of John C. Fremont in the 1856 Presidential election demonstrated it dominated most northern states. Early Republican ideology was reflected in the 1856 slogan "free labor, free land, free men."[3] "Free labor" referred to the Republican opposition to slave labor and belief in independent artisans and businessmen. "Free land" referred to Republican opposition to plantation system whereby the rich could buy up all the good farm land and work it with slaves, leaving the yeoman independent farmers the leftovers. The Party had the goal of containing the expansion of slavery, which would cause the collapse of the Slave Power and the expansion of freedom.[4] Lincoln, representing the fast-growing western states, won the Republican nomination in 1860 and subsequently won the presidency. The party took on the mission of saving the Union and destroying slavery during the American Civil War and over Reconstruction. In the election of 1864, it united with pro-war Democrats to nominate Lincoln on the National Union Party ticket.

So the anti-slavery stance was more economic than moral or religious. But the religious aspect help the party politally so they embraced it as well.

The party's success created factionalism within the party in the 1870s. Those who felt that Reconstruction had been accomplished and was continued mostly to promote the large-scale corruption tolerated by President Ulysses S. Grant ran Horace Greeley for the presidency. The Stalwarts defended Grant and the spoils system; the Half-Breeds, pushed for reform of the civil service. The GOP supported business generally, hard money (i.e., the gold standard), high tariffs to promote economic growth, high wages and high profits, generous pensions for Union veterans, and (after 1893) the annexation of Hawaii. The Republicans supported the pietistic Protestants who demanded Prohibition.

As the Northern post-bellum economy boomed with heavy and light industry, railroads, mines, fast-growing cities and prosperous agriculture, the Republicans took credit and promoted policies to sustain the fast growth. Nevertheless, by 1890 the Republicans had agreed to the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Interstate Commerce Commission in response to complaints from owners of small businesses and farmers. The high McKinley Tariff of 1890 hurt the party and the Democrats swept to a landslide in the off-year elections, even defeating McKinley himself.

After the two terms of Democrat Grover Cleveland, the election of William McKinley in 1896 is widely seen as a resurgence of Republican dominance and is sometimes cited as a realigning election. McKinley promised that high tariffs would end the severe hardship caused by the Panic of 1893, and that the GOP would guarantee a sort of pluralism in which all groups would benefit. The Republicans were cemented as the party of business, though mitigated by the succession of Theodore Roosevelt who embraced trust busting. He later ran on a third party ticket of the Progressive Party and challenged his previous successor William Howard Taft. The party controlled the presidency throughout the 1920s, running on a platform of opposition to the League of Nations, high tariffs, and promotion of business interests. Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover were resoundingly elected in 1920, 1924, and 1928 respectively. The Teapot Dome scandal threatened to hurt the party but Harding died and Coolidge blamed everything on him, as the opposition splintered in 1924. The pro-business policies of the decade seemed to produce an unprecedented prosperity until the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the Great Depression.

As you can see the political agenda of any party depends to a large extent on the situation. But one thread seems to be present in all the parties is that until the FDR administration during the Great Depression, social justice and individual liberties were not a major consideration for any of the political parties. In fact the constitutional interpretation by the supreme court put property rights and business contracts ahead of any personal considerations especially concerning immigrants and ethnic minorities. And remained this way until FDR threatened to pack the court with 6 additional judges of his own choosing to make sure non of his legislation got over turned by the bench.

Our current social and political agenda of social, civil and economic justice for each individual is a fairly current situation. And to try and define any political party by any one encompassing agenda is not well served. Neither party is terribly reminiscent of it's origins and will most like evolve to something totally different in the future or be replaced.

No comments:

Post a Comment